Mosquito-borne transmission of the Zika virus appeared in South Florida just recently, but at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, forward-thinking researchers and clinicians had begun preparing for its arrival a year ago.

That’s when David Watkins, Ph.D., vice chair for research in the Department of Pathology who researches diseases in Latin America where the infections were reaching epidemic proportions, first sounded the alarm about the potential consequences in South Florida.

He was correct to be concerned: There are now 42 confirmed locally acquired infections; and the first one in Pinellas County, on Florida’s west coast, was just confirmed.

|

| Christine L. Curry, M.D., Ph.D., assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology, is treating and counseling women infected with Zika. |

Watkins’ colleagues heeded his call months before the World Health Organization declared Zika an international public health emergency, and before experts confirmed the virus was responsible for the surging number of newborns with abnormally small heads. They stopped thinking of Zika as a potential travel risk and began preparing to battle a possible outbreak here at home.

As a result, UHealth physicians are already busy counseling prospective parents and treating pregnant women, and UM scientists are working overtime to bring diagnostic and therapeutic responses from the laboratory to the clinic — some possibly by the end of this year.

Testing for the threat

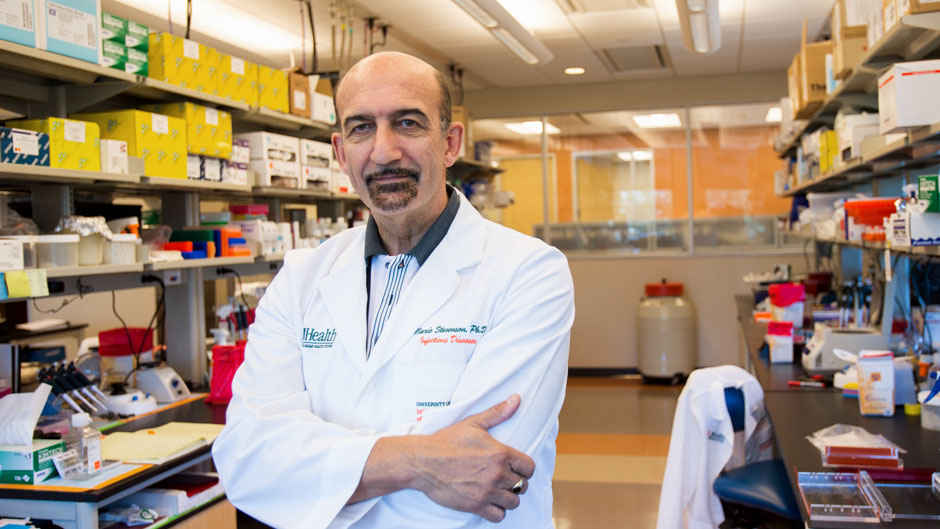

One of them is Mario Stevenson, Ph.D., professor of medicine, chief of the Division of Infectious Diseases and director of the Institute of AIDS and Emerging Infectious Diseases, whose laboratory has developed a diagnostic blood test for Zika that costs a fraction of current tests, delivers results quickly, and can be performed on the spot in any hospital or outpatient clinic.

Right now the seven currently approved tests cost $100 to $150, have to be evaluated in a commercial laboratory, and require a wait of several days before a patient receives the results.

“That’s far too expensive for a couple in a developing country who want to have children — especially if they require multiple testing — and far too long for them to wait to learn if one of them is carrying the virus, which experts now know can be transmitted through sex,” said Stevenson. “Even here in Florida, where the Department of Health is offering free testing, the growing demand is putting a real time strain on the few laboratories that do the work.”

Zika was first isolated in 1947 and long considered benign and confined to Africa – its name comes from the Zika Forest in Uganda.

Stevenson’s extremely sensitive test, which can detect the DNA of the Zika virus at the earliest stage of infection, would cost about one-tenth of current tests, with results ready in an hour. An investor is already waiting to market the test, and the only remaining hurdle is the application for FDA approval.

Watkins and two researchers from the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology — Sylvia Daunert, Pharm.D., M.S., Ph.D., professor and holder of the Lucille P. Markey Chair, and Sapna Deo, Ph.D., M.S., associate professor, and their team — have developed an even simpler, cheaper test. Potentially priced as low as $2, it requires no processing from a lab. Using a paper strip containing selective antibodies from the Watkins lab that bind to the virus obtained from Zika-infected patients, it delivers a simple “yes” or “no” verdict as to whether the virus is present, or whether the patient has ever been exposed to it.

“It’s completely simple,” said Daunert. “It can be used either in a physician’s office or by health care workers in remote rural locations where there are no hospitals or clinics. But in the process we are also developing a platform that can be customized for different viruses — it’s not just for Zika — because different ones are going to keep popping up.”

After completing the test development, which is still several months away, Watkins and Daunert will apply for a patent and begin seeking investors to bring it to market.

Preventing a pandemic

Watkins, working with Miller School colleague Ronald C. Desrosiers, Ph.D., professor of pathology, and investigators at the University of São Paulo, Brazil, and the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, Calif., is also taking a preventive approach using antibodies from Zika patients.

“We could inject the antibodies into a woman prior to pregnancy to protect both the mother and the fetus,” he said, “or it could be done after infection, when it would bind to the virus and reduce replication.”

Still, he said, “therapeutic antibodies need to go through Phase I and Phase II trials, which will take one or two years. It’s not a quick fix.”

Another Miller School researcher is taking a classic vaccine approach, with a novel twist.

“Rather than using an attenuated live virus for vaccinations — an approach used for decades with other diseases, but which carries some risk — a Zika vaccine would incorporate only certain components of the virus, specifically the envelope portion, for patient safety,” said Glen N. Barber, Ph.D., chair of the Department of Cell Biology. “We are also looking at the mechanisms of how Zika overcomes the immune system to infect the host.”

Barber, however, believes developing the vaccine won’t be the hardest part of the task.

“I think it will be relatively easy to develop a vaccine,” he said, “and the animal studies will be completed this year. What will be more difficult will be determining how to scale up for vaccinating the population at large.”

Physicians on the front lines

In UM’s clinics, where UHealth physicians are on the front lines in the fight against Zika, obstetricians and gynecologists have been caring for pregnant women who were infected with Zika both abroad and at home. Now they are gearing up to expand their services.

“We are beginning a wrap-around neonatal and pediatric care clinic for women who have been infected with Zika during their pregnancies to ensure that during pregnancy and after delivery mothers and infants receive the care that they need,” said Christine L. Curry, M.D., Ph.D., assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology, who over the months has had many conversations “with men, pregnant women and non-pregnant women about mosquito-bite prevention and prevention of sexual transmission.

“They’ve heard about it on the news and are asking what they can do to prevent Zika infection, either during pregnancy or before pregnancy,” she said. “If women are pregnant and living in Miami, we want them to avoid, if feasible, the areas where we know mosquito-borne Zika virus transmission is ongoing, so currently that’s Wynwood and parts of Miami Beach. In addition, no matter where they live or work in the city, we want them to wear mosquito repellant every time they leave the house, long pants and long sleeves, and do their best to remove all the standing water in their neighborhood. For both the partners and the patients, the exact same advice holds.”

Curry notes that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that women delay conception for two months from the time of a known or suspected Zika infection, and that men wait at least six months.

As such, she encourages women who are pregnant to be tested for Zika, and those who are planning a pregnancy to consult with their primary care provider. She recommends anyone who is experiencing Zika symptoms — fever, joint pain, muscle pain, red eyes or a rash — be evaluated by their primary care provider or at the emergency room.

Gearing up for the Zika virus on the clinical side has required many meetings and phone conferences within and among leaders of UHealth, Jackson Memorial Hospital and the VA Medical Center. Thomas M. Hooton, M.D., professor of clinical medicine and Medical Director of UHealth Infection Control, says dealing with all potentially large-scale public health threats ultimately comes down to two elements — education and communication.

“In the case of Zika virus, we must first educate our physicians and employees about how to keep themselves safe — personal protection and environmental issues — so they can be protected,” he said. “That includes our employees who work outdoors, and we have been providing special guidance to them.

“Then, on the clinical side, we also need to educate all clinicians and staff about how to identify, counsel and treat patients who may have Zika based on their symptoms or travel history. We also need to educate our patients to heighten their awareness about Zika and to encourage them to let their provider know of any concerns or questions they may have.”

Other concerns, which have received little media attention, he notes, include the blood supply, organ donation and in vitro fertilization.

“These are the issues that keep us talking to one another,” Hooton said. “Continued education and communication, until long-term solutions can emerge from the lab, are critical in keeping the Zika threat under control.”

Talking to the kids

Communication and education are also essential for parents and school officials who, in the face of the Zika threat, may be dealing with more than the normal back-to-school anxieties. Jill Ehrenreich-May, associate professor of psychology in the College of Arts and Sciences, says that even in the face of perceived danger, such as having a pregnant mom who needs to stay indoors, parents should reassure their children that the adults have everything covered.

“If a parent responds to the threat of Zika by hiding in the house and worrying about every puddle of water on the ground, the impact is probably going to feel bigger, more intense, and more problematic to both the parent and child,” she said. “If the threat isn’t acute to you or your family, it is important to be mindful that you as a parent are not accidentally reinforcing unnecessary avoidance behavior.”

The economic impact

Local and state officials are understandably jittery over the potential impact the locally transmitted outbreak could have on Miami-Dade County’s $36 billion tourism industry, and beyond.

Arun Sharma, Ph.D., professor of marketing at the UM School of Business Administration, expects it to be minimal since the greatest risk is to pregnant women, or those expecting to get pregnant. For now, the CDC is advising pregnant women and those planning a pregnancy to avoid Miami-Dade County altogether, so, Sharma said, “most tourists shrugged off the possible effects of Zika.”

But new concerns about Zika are being raised almost on a daily basis. CDC Director Tom Frieden noted that aerial spraying cannot be conducted amid high rises and sea breezes, so fighting Zika on Miami Beach will be more challenging than in Wynwood. A recent medical research report based on experiments on mice suggests that Zika may also affect adult brain cells critical to learning and memory.

And, if the outbreak grows, news about Zika on South Florida’s most popular tourist destination will continue to be broadcast across the country and around the world.

“So, what are the expectations for tourism and the local economy?” Sharma asked. “In the short-term it should be minimal. However, if the negative coverage of Zika in Miami increases and/or if countries start providing travel advisories suggesting that their citizens not visit Miami, the drop in tourism may be steep, negatively affecting the economy. The concern is not the young who will continue coming. The concern is the middle-aged and older tourists who typically are more sensitive to health issues and may avoid Miami.”

But for Curry and other public health specialists, the Zika virus must be everybody’s concern and responsibility.

“While there is a focus on prevention of Zika in pregnancy, it’s the responsibility of every one of us to wear our bug spray, to wear our long sleeves and long pants, and to remove standing water because we cannot protect the pregnant women in our community if we are not all doing our part,” Curry said.

Alex Bassil and Jennifer Palma contributed to this report.